Bazaar: The word, for most Westerners, conjures up visions of fund-raising

events, neighborhood carnivals and church socials. However, the word itself

comes from the Middle East, and it is there one must go to sample the full

flavor of this unique and colorful Middle East institution of marketing.

During the course of a recent visit to Iran I had an opportunity to visit

one of the largest bazaars in the world, that in the city of Teheran. Oddly

enough, my visit was not made in the company of an Iranian, but a German

who makes a very comfortable living as an exporter of the fabled Persian

carpets (Germans are among the most discriminating and largest buyers of

Persian carpets in the world).

The first impression one receives of the bazaar is that it is a sort of

vast, subterranean market place; acres and acres of shops and stalls packed

together, lining murky dirt streets covered by flimsy wooden canopies with

electric wiring that is a fire inspector's nightmare.

In fact, there is not one bazaar, but several, all located in the same

general area. There is the rug bazaar, consisting of dozens of stalls.

Since there is such great similarity between carpets, it is difficult to

guess just how all of these merchants manage lo make a living; there is no

advertising, no raspy-throated hawkers, nothing to help the uninitiated

distinguish one seller's pro-rliict from another.

And if any of the merchants are economically hard pressed they give no

evidence of it. They sit and wait patiently for customers, talking and

drinking hot chai (tea) with their friends. For the average Westerner,

accustomed as he is to high-pressure sales tactics, a visit to the bazaar

will be a most refreshing experience.

When my wife (who is Iranian) and I expressed a desire to buy a carpet, we

were taken by friends to one of the better carpet shops in the bazaar. The

showroom was large, airy, and filled with hundreds of carpets of varying

sizes and quality, all neatly folded and placed one on top of another. We

indicated the type of carpet we were looking for, and what we wanted to

pay, then sat down in one corner of the room while two young workers began

the laborious task of displaying the carpets.

Rugs are not paintings; there is no way all of them can be shown at one

time. Each rug must be unfolded from its pile and laid out before the

potential customer. Since there were so many carpets to choose from, it

took the young men almost three hours to lay out, one by one, the carpets

we wished to look at. Not once did the men exhibit any impatience with

their tiring task. Unfortunately, we could not find a carpet we wanted

and—somewhat guiltily—said so. The men and the owner thanked us

profusely, despite the fact that we had bought nothing.

Iranian merchants arc extremely gracious (as are the people generally). Had

we expressed only uncertainty about one particular carpet, the owner

immediately would have offered to allow us to take the carpet home with us

(even to the US!) fur a "trial" lasting an unspecified length of time. No

credit card is needed, and no bank rating required. We could simply walk

off with a $100 carpet under our arm, put it on our floor for days, weeks,

months: then return it if we decided we didn't want it. No questions asked.

This practice is not rare, it is commonplace.

The rug merchant knows better than anyone else that a Persian carpet has a

very mysterious, almost magical, way of working its way into the heart of

its owner. He knows that a man or woman, once having lived with a carpet,

will, nine times out of ten, decide to buy. An added bonus is that Persian

carpets become more valuable as they grow old. Some of the best—and most

valuable—antique carpets are to be found in the United States. However,

they are not always appreciated by Americans and thus can often be bought

at bargain prices. In fact, recently, Iranian rug merchants have made trips

to the United States to buy Persian Carpets for resale—at a large

profit—in Iran!

The air of the bazaar is filled with the heady smell of cooking chelo kebab

(rice and lamb). Men stagger under their load of carpets which they carry

on special racks they carry on their backs, human "mules" who transport

piles of goods from one stall to another as sales or exchanges are made.

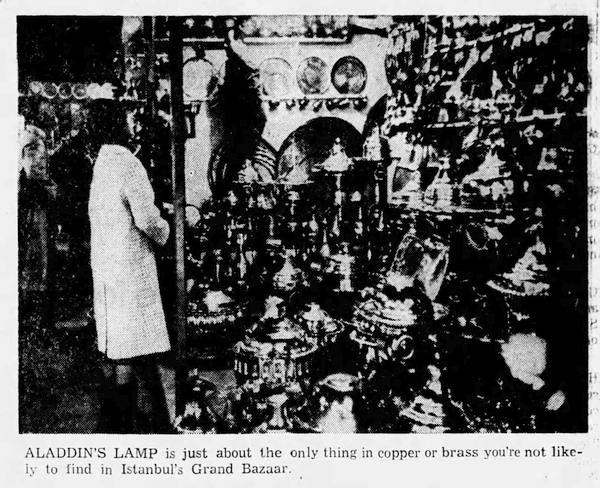

A few hundred feel down the street the rug bazaar suddenly becomes

the metal-goods bazaar, and the soft, earth colors of the carpets are

replaced by the sheen of metal goods, some new.

For the expert, there are many excellent buys in the metal bazaar, very old

(hence very valuable) pieces of jewelry or pottery, artifacts dug from the

ruins of Persepolis, handed down from generation to generation, then

bartered at the bazaar when money was needed. Some of these pieces would

not be out of place in a museum. Of course, there is also much

that is junk, but one cannot help but feel an air of excitement, stimulated

by the knowledge that some of those tiny trinkets haphazardly piled in trays

may be of great value, especially when resold back in the United States.

Then there is the shoe bazaar, and the house-wares bazaar: goods of every

shape and variety. In short, wherever one goes in this very special place,

the sights and rounds and smells of the bazaar are not easily forgotten.